The Japanese tea ceremony, also called the Way of Tea, is a Japanese cultural activity involving the ceremonial preparation and presentation of matcha(抹茶), powdered green tea. 茶の湯 Japanese, it is called chanoyu (茶の湯) or sadō, chadō (茶道), while the manner in which it is performed, or the art of its performance, is called (o)temae([お]手前; [お]点前). Zen Buddhism was a primary influence in the development of the Japanese tea ceremony. Much less commonly, Japanese tea practice uses leaf tea, primarily sencha, in which case it is known in Japanese as senchadō (煎茶道, the way of sencha) as opposed to chanoyu or chadō.

Tea gatherings are classified as an informal tea gathering chakai (茶会, tea gathering) and a formal tea gathering chaji (茶事, tea event). A chakai is a relatively simple course of hospitality that includes confections, thin tea, and perhaps a light meal. A chaji is a much more formal gathering, usually including a full-course kaiseki meal followed by confections, thick tea, and thin tea. A chajican last up to four hours.

Chadō is counted as one of the three classical Japanese arts of refinement, along with kōdō for incense appreciation, and kadō for flower arrangement.

There are two main ways of preparing matcha for tea consumption: thick (濃茶 koicha) and thin (薄茶 usucha), with the best quality tea leaves used in preparing thick tea. Historically, the tea leaves used as packing material for the koicha leaves in the tea urn (茶壺 chatsubo) would be served as thin tea. Japanese historical documents about tea that differentiate between usucha and koicha first appear in the Tenmon era (1532–55). The first documented appearance of the term koicha is in 1575.

As the terms imply, koicha is a thick blend of matcha and hot water that requires about three times as much tea to the equivalent amount of water than usucha. To prepare usucha, matcha and hot water are whipped using the tea whisk (茶筅 chasen), while koicha is kneaded with the whisk to smoothly blend the large amount of powdered tea with the water.

Thin tea is served to each guest in an individual bowl, while one bowl of thick tea is shared among several guests. This style of sharing a bowl of koicha first appeared in historical documents in 1586, and is a method considered to have been invented by Sen no Rikyū.

The most important part of a chaji is the preparation and drinking of koicha, which is followed by usucha. A chakai may involve only the preparation and serving of thin tea (and accompanying confections), representing the more relaxed, finishing portion of a chaji.

Tea equipment is called chadōgu (茶道具). A wide range of chadōgu are available and different styles and motifs are used for different events and in different seasons. All the tools for tea are handled with exquisite care. They are scrupulously cleaned before and after each use and before storing, and some are handled only with gloved hands. Some items, such as the tea storage jar "Chigusa," were so revered that they were given proper names like people and were admired and documented by multiple diarists.

The following are a few of the essential components:

Chakin (茶巾). The "chakin" is a small rectangular white linen or hemp cloth mainly used to wipe the tea bowl.

Tea bowl (茶碗 chawan). Tea bowls are available in a wide range of sizes and styles, and different styles are used for thick and thin tea. Shallow bowls, which allow the tea to cool rapidly, are used in summer; deep bowls are used in winter. Bowls are frequently named by their creators or owners, or by a tea master. Bowls over four hundred years old are in use today, but only on unusually special occasions. The best bowls are thrown by hand, and some bowls are extremely valuable. Irregularities and imperfections are prized: they are often featured prominently as the "front" of the bowl.

Tea caddy (棗・茶入 Natsume・Chaire). The small lidded container in which the powdered tea is placed for use in the tea-making procedure ([お]手前; [お]点前; [御]手前 [o]temae).

Tea scoop (茶杓 chashaku). Tea scoops generally are carved from a single piece of bamboo, although they may also be made of ivory or wood. They are used to scoop tea from the tea caddy into the tea bowl. Bamboo tea scoops in the most casual style have a nodule in the approximate center. Larger scoops are used to transfer tea into the tea caddy in the mizuya (preparation area), but these are not seen by guests. Different styles and colors are used in various tea traditions.

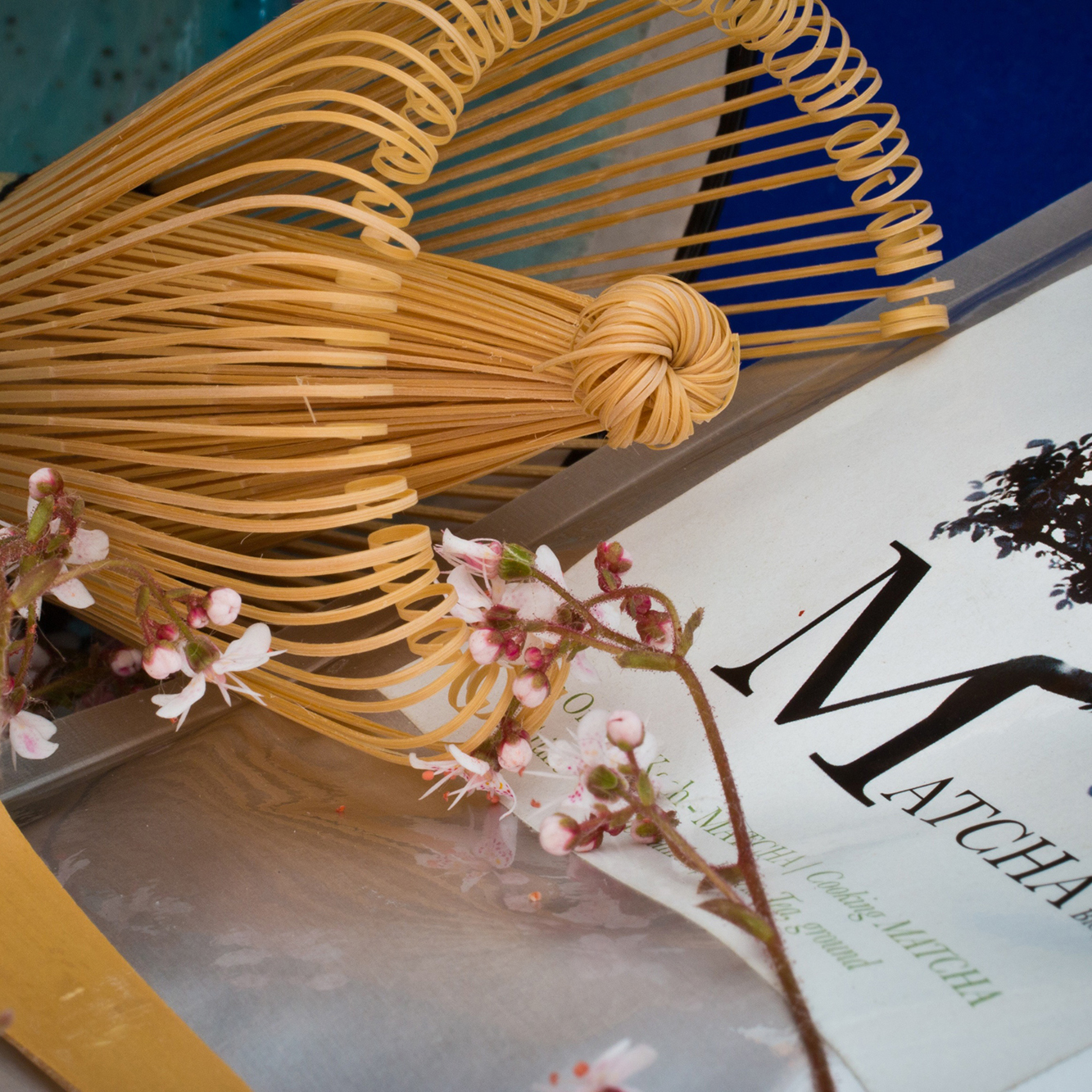

Tea whisk (茶筅 chasen). This is the implement used to mix the powdered tea with the hot water. Tea whisks are carved from a single piece of bamboo. There are various types. Tea whisks quickly become worn and damaged with use, and the host should use a new one when holding a chakai or chaji.

Procedures vary from school to school, and with the time of year, time of day, venue, and other considerations. The noon tea gathering of one host and a maximum of five guests is considered the most formal chaji. The following is a general description of a noon chaji held in the cool weather season at a purpose-built tea house.

Ideally, the waiting room has a tatami floor and an alcove (tokonoma), in which is displayed a hanging scroll which may allude to the season, the theme of the chaji, or some other appropriate theme. The guests are served a cup of the hot water, kombu tea, roasted barley tea, or sakurayu. When all the guests have arrived and finished their preparations, they proceed to the outdoor waiting bench in the roji, where they remain until summoned by the host.

Following a silent bow between host and guests, the guests proceed in order to a tsukubai (stone basin) where they ritually purify themselves by washing their hands and rinsing their mouths with water, and then continue along the roji to the tea house. They remove their footwear and enter the tea room through a small "crawling-in" door (nijiri-guchi) and proceed to view the items placed in the tokonoma and any tea equipment placed ready in the room and are then seated seiza-style on the tatami in order of prestige. When the last guest has taken their place, they close the door with an audible sound to alert the host, who enters the tea room and welcomes each guest, and then answers questions posed by the first guest about the scroll and other items.

The chaji begins in the cool months with the laying of the charcoal fire which is used to heat the water. Following this, guests are served a meal in several courses accompanied by sake and followed by a small sweet (wagashi) eaten from special paper called kaishi (懐紙), which each guest carries, often in a decorative wallet or tucked into the breast of the kimono. After the meal, there is a break called a nakadachi (中立ち) during which the guests return to the waiting shelter until summoned again by the host, who uses the break to sweep the tea room, take down the scroll and replace it with a flower arrangement, open the tea room's shutters, and make preparations for serving the tea.

Having been summoned back to the tea room by the sound of a bell or gong rung in prescribed ways, the guests again purify themselves and examine the items placed in the tea room. The host then enters, ritually cleanses each utensil—including the tea bowl, whisk, and tea scoop—in the presence of the guests in a precise order and using prescribed motions, and places them in an exact arrangement according to the particular temae procedure being performed. When the preparation of the utensils is complete, the host prepares thick tea.

Bows are exchanged between the host and the guest receiving the tea. The guest then bows to the second guest, and raises the bowl in a gesture of respect to the host. The guest rotates the bowl to avoid drinking from its front, takes a sip, and compliments the host on the tea. After taking a few sips, the guest wipes clean the rim of the bowl and passes it to the second guest. The procedure is repeated until all guests have taken tea from the same bowl; each guest then has an opportunity to admire the bowl before it is returned to the host, who then cleanses the equipment and leaves the tea room.

The host then rekindles the fire and adds more charcoal. This signifies a change from the more formal portion of the gathering to the more casual portion, and the host will return to the tea room to bring in a smoking set (タバコ盆 tabako-bon) and more confections, usually higashi, to accompany the thin tea, and possibly cushions for the guests' comfort.

The host will then proceed with the preparation of an individual bowl of thin tea to be served to each guest. While in earlier portions of the gathering conversation is limited to a few formal comments exchanged between the first guest and the host, in the usucha portion, after a similar ritual exchange, the guests may engage in casual conversation.

After all the guests have taken tea, the host cleans the utensils in preparation for putting them away. The guest of honor will request that the host allow the guests to examine some of the utensils, and each guest in turn examines each item, including the tea caddy and the tea scoop. The items are treated with extreme care and reverence as they may be priceless, irreplaceable, handmade antiques, and guests often use a special brocaded cloth to handle them.

The host then collects the utensils, and the guests leave the tea house. The host bows from the door, and the gathering is over. A tea gathering can last up to four hours, depending on the type of occasion performed, the number of guests, and the types of meal and tea served.